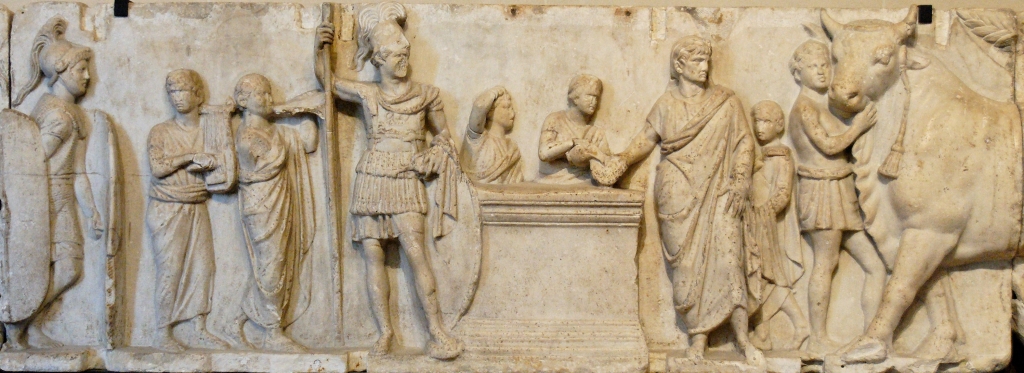

Relief from the “Altar” of Domitius Ahenobarbus (late 2nd century BC): This relief was found in the Campius Martius (Field of Mars) section of Rome. Some scholars believe the relief was part of an altar, while others (including those at the Louvre, where the relief is currently housed) think it was placed on the base of a group of statues in a temple. It is often associated with Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (died ca. 104 BC). Consul in 122 BC, he defeated the Gauls in southern France on several occasions. He was most famous for helping construct the Via Domitia, the famous Roman road that linked Italy and Spain. This image is a detail of a relief that commemorates the census ceremony in which citizens were enrolled in the Roman army with their wealth determining the kind of unit to which they were assigned. The ceremony culminated in the sacrifice of a bull, a ram, and pig to Mars, the god of war. In this image, we get a good idea of what a Roman soldier would have looked like in the late Republic around the time of Marius’ reforms. Note the long four-foot shield with the rounded edges as well as the chain mail armor.

Reading

Please read pages 117-131 and 144-145 in the textbook.

Course Themes

As always, you should think about the course themes (innovation, capacity, calculation, and culture) and how they relate to today’s reading. You should also consider the 5 C’s of historical thinking (change over time, causality, context, complexity, and contingency) and how you can apply them to what you just read.

What We are Doing Today

Lee is interested in analyzing the “intractable security issues” that empires face. How does an imperial government obtain reliable and responsive troops to guard far-flung frontiers? Neither Rome nor Han China were the first to confront or resolve these issues. Others, including the Babylonian, Hittite, Assyrian, and Persian empires, had wrestled with this problem earlier. However, Han China and especially Rome proved particularly adept at dealing with this question. And interestingly enough, these two empires, which were contemporaries, came to terms with this difficulty in much the same way.

Today, we will deal with Rome. Keep in mind that Lee is dealing with something intangible—discipline. We are not discussing a weapon system like the chariot that has a single point of origin (Chapter 2). Indeed, we are analyzing something akin to the Greek phalanx (Chapter 3). Lee is not so much interested in the weapons that the soldiers bore; rather, he is much more intrigued by the spirit or culture that motivated the soldiers themselves. There are other parallels that we can draw between this chapter (Chapter 4) and Chapter 3. For example, the nature and motives of the Greek phalanx changed over time, particularly in the switch from the classical Greek version to the Macedonian iteration. So too did Roman notions of discipline which changed when one compares the army of the Republic before Marius’ reform and the army that came after, mainly under the Empire.

As you read this section about the Romans, it might help to keep the Greeks in mind. For sure, you should compare Lee’s approach in both chapters—after all, both have much to do with culture. Lee himself makes such comparisons. See p. 127, where he actually compares the hoplite phalanx to the professional army of the Roman Empire:

Ironically, Roman collective training was applied to weapons often thought of as individualistic: the sword and javelin. The hoplite phalanx depended on truly mutual effort for its effect. That mutuality, however, was achieved not by professionals but by amateurs in a kind of “undisciplined corporatism.” In contrast, the Roman system took men armed with individualistic weapons and multiplied their effect through training in collective action; in another shorthand, they were “disciplined individualists.”

And we can see the collective action of disciplined individualists below.

Spartacus (1960): This Stanley Kubrick film revolves around a slave revolt led by Spartacus against the Romans in 73 BC. Kubrick was always anxious to get the history right, and in this scene, while showing the Roman army deploying against the slaves, we see one interpretation of what the triplex acies or Roman battle order looked lie and how it worked. The quincunx formation is very apparent. Most important for our purposes, though, is the idea conveyed in this clip of Roman soldiers trained to fight like individuals with javelin and sword—but as part of a greater whole bound together in a complex formation.

Periodizing Rome’s Story

It might help a little if we chop up Roman history into bite-sized pieces by periodizing it. The Roman Republic was traditionally founded in 509 BC when the Romans overthrew their last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. The greatest power in the Republic was the Senate, which consisted of aristocrats, but as Lee points out, the common people, the plebeians, gained more status as time went on, and legal equality was achieved by 287 BC.

As you will see in the text, the military reforms of Gaius Marius (ca. 107 BC) both reflected and caused major changes in Roman politics. A series of civil wars ensued, and at the end of it all, Octavius (who assumed the title of Augustus) emerged as the supreme ruler of Rome in 27 BC. The Roman Empire emerged as a result.

Rome at the Time of Gaius Marius: The green sections show the extent of the Roman Republic more or less at the end of the second Punic War. The orange sections were added over the course of the 2nd century BC. The two together represent what the empire looked like roughly in Gaius Marius’ time (157 BC-86 BC). Although Roman military service changed repeatedly over a long period of time, Marius instituted a number of significant reforms. It was clear at this point that the old militia of citizen-soldiers was not adequate to maintain or expand the Republic’s growing territories. Soldiers shipped off to Spain, Gaul, North Africa, or Asia Minor for a number of years could not look after their farms. Something different and more professional was needed, and Marius provided it. But in so doing, he helped transform the type of men recruited and the nature of Roman military service.

After Augustus assumed power, Roman imperial expansion slowed. As Lee points out, there were some changes: Britain was conquered, there were advances (and retreats) in the Near East, and the position along the Danube River shifted. All in all, however, the frontiers became more static.

As we discuss frontiers, we ought to remember that, as Lee claims, they were frequently not fortified. Indeed, the frontiers were rather porous—lots of people crossed the frontiers every day. The Romans controlled their boundaries through a variety of tools including bribes, alliances, and force.

So to recapitulate:

- 509 BC: Roman Republic founded

- 107 BC: Marius’ reforms

- 27 BC: Octavius/Augustus founds Roman Empire

- 100 AD: Roman imperial expansion more or less ends

Gladiator (2000): Far be it from me to say that Gladiator is historically accurate (it’s not). In fact, it places people together who were actually years and years apart. It suffices to say that the film takes place at some point in the late 2nd or earlier 3rd century AD. This is the fully professional army associated with imperial Rome. I’d like to think that this scene captures the disciplina of that army as compared to the wild individual courage of the Germans. Here, the Romans do not express the aggressive individualism of the citizen-soldiers who served under the Republic. Rather, these soldiers of the Empire are obedient, and that obedience is the result of long training. They immediately respond to their officers’ commands, and as they advance, they do so in formation, with no one ahead or behind anybody else. The formation changes promptly in reaction to threats.

Potential Quiz Questions

NOTE: Do not get bogged down in the details about how the manipular or cohort legion worked. Think more about the spirit that inspired these units; that is, after all, Lee’s main point.

1) Explain concisely what ideas each of the three paragraphs in the introduction of the chapter seeks to convey.

2) What were the “key characteristics” of the Roman Republic’s approach to war that contributed to military victory and/or social peace? Briefly explain how each made Rome more militarily effective and stable.

3) Originally, under the Republic, what were fama, disciplina and virtus? Why were they so important among the citizen-soldiers of the Republican army. How were these balanced and accommodated within the Roman legion during this period?

4) What were the two major reforms that Gaius Marius implemented in the Roman army? (One was tactical, the other about recruiting.) What were the important consequences of these reforms?

5) Under the Empire, how did disciplina change, and how did it resolve the “critical problems of an expansive agricultural empire?”

6) What was the purpose of limes?

Hadrian’s Wall, England (ca. 120 AD): This wall, which separated Roman England from what is now Scotland, is the best preserved frontier left behind by the Roman Empire. The Romans had begun the conquest of southern England in 43 BC. By the mid 80s, the Romans had pushed well into Scotland, winning (supposedly) a great battle against the Caledonii at Mons Graupius in 83 or 84. Sustaining an occupation of Scotland, however, proved beyond the Romans, and starting around 120 under Emperor Hadrian, they began to build a wall across what was the narrowest part of northern England—an 80-mile stretch of land between Solway Firth in the west and the mouth of the Tyne River in the east. This line of fortifications pretty much followed a frontier road called the Stanegate. Scholars have argued over the purpose of the wall which remains unclear. Mary Beard, one of the world’s leading historians of Rome, writes in reference to the wall that “it is surprisingly hard to know what exactly it was for.” “It could hardly have deterred any reasonably spirited and well-organized enemies who were keen to scale it,” she continues, and “it was not even well designed for surveillance and patrol purposes.” At the same time, it was far too “hefty” to serve as a “customs barrier” or as “an attempt to control the movement of people.” Beard concludes: ” What it asserts is Roman power over the landscape while also hinting at a sense of ending. It may be no coincidence that other, rather less dramatic walls, banks and fortifications were developed in other frontier zones at roughly the same period, as if to suggest that the boundaries of Roman power were beginning to take a more physical form.” For more information about the wall, check out Hadrian’s Wall Country and the English Heritage site on Hadrian’s Wall.